I watched the new movie by Michael Moore entitled “Sicko” this past weekend. Although it is not due out in theaters for several weeks, it was “leaked” onto the web and is being freely downloaded by thousands of people. Interestingly, Mr Moore does not seem too upset by this turn of events. In fact, he has endorsed it. You can view the below Google Video of an interview with him where he states...

I don't agree with copyright laws and I don't have a problem with people downloading the movie and sharing it...as long as they're not trying to make a profit off my labor... I make these movies and books and TV shows because I want things to change, and so the more people who get to see them, the better.

Given his public statements on the issue, some have speculated that Mr Moore himself is responsible for the leak. There is no way to know whether this is true or not, but at the very least Mr Moore clearly has no problem with us downloading pirated copies of his movie.

So, with that disclaimer out of the way, lets take a look at the substance of “Sicko”. In this movie, Mr Moore attempts to make a case for national health insurance. This is not going to be a movie review -- Mr Moore is clearly an accomplished filmmaker -– rather, I want to examine the specific issues he raises in the film and whether he presents a compelling case for the US adopting a form of national health insurance.

The central theme of “Sicko” is that US health insurance companies care more about profits than about people. He paints a picture of a world in which people who are seriously ill cannot count upon their health insurance to pay for expensive medical care. Conversely, in countries with national health insurance, people have access to free on-demand state-of-the-art medical care as a right of citizenship. Aside: The word "free" (as in beer) is used repeatedly in the movie, only occasionally being qualified. Of course, nothing in the Real World® is ever free, and that is at the crux of this entire debate, but more on that in a moment.

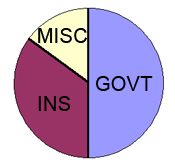

I think the first order of business is to put things into some perspective. The largest provider of health insurance in the US is already the government (source). Medicare, Medicaid, and other State and Federal programs account for approximately 50% of all health care expenditures in the United States. Private health insurance accounts for 35% of the total health care pie (see figure). The other 15% coming from other private sources, such as philanthropy. Private health insurance primarily covers young people with families during their working years. After retirement, Medicare, not private insurance, pays for most care. The indigent are covered by Medicaid. The point being that this entire discussion is addressing only about one-third of all healthcare expenditures in this country. The balance of which, for the most part, is already covered by government programs.

The nightmare scenario that “Sicko” portrays is when a young person contracts a catastrophic illness, such as cancer. The cost of such a disease quickly exceeds the resources of an average family, and therefore the person is at the mercy of their health insurance company to pay the bills. “Sicko” depicts the interests of health insurance companies and their customers as being at odds, with the insurance company seeking to deny coverage or cancel policies whenever expensive care is needed. In actuality, only 14% claims were denied in 2006 (source). Half of these denials were the result of duplicate claim submission, incomplete information, or coding errors. That leaves 7% of all health insurance claims being denied due to coverage-related issues. Upon denial, consumers can appeal the decision to internal and external review boards (source). Federal law requires an internal review process for individuals who appeal a denied benefit claim. Beyond that requirement, 45 States have requirements for independent external review processes for health insurers, whereby denials of health insurance coverage are reviewed by physicians who are unaffiliated with their health plan. In addition, most States have patient protections that allow direct access (without prior approval) to certain health care providers and services. Federal law ensures public access to emergency services regardless of ability to pay (source). A recent research study examining claim denials in a period between 2001-2002 found that 20% of appeals involved experimental/investigational treatments; the remainder involved issues of medical necessity. External review overturned the health plan denial in 41% of medical necessity appeals and 20% of experimental/investigational appeals. Therefore, it is an exceedingly rare occurence that a doctor will recommend a treatment and the patient's health insurance does not pay for it, even if they initially deny the claim.

Health insurance companies are not the only target in “Sicko”. Pharmaceutical companies are also depicted as profiteering. Much has been made of the large difference in cost of drugs within the US and abroad. It is true that the same drug can cost much less in Canada (or Cuba, as was the case in the movie) than in the US. Why is that? The answer is that the cost of a drug in the US is the true cost, while the cost elsewhere is an artificially reduced price (source). The true cost of a product must incorporate the cost of research and innovation. If a drug company is to survive it must recoup the cost of developing a pharmaceutical, and invest money in developing its next product. For example, a copy of Microsoft Vista costs hundreds of dollars within the US, yet a copy can be had on the streets of China for just a few dollars. Because the CDs upon which it is printed costs pennies, pirates can copy and sell Microsoft Vista at a profit for a few dollars. Yet nobody could produce it from scratch and then sell it at such a low price. The same is true of drugs. It is possible for them to copy and sell generic versions of US-developed drugs at very little cost, but don’t count on the Canadians drug companies to come up with a cure for cancer or develop a treatment the next AIDS, SARS, or bird flu.

I am not arguing that the American health care system is perfect. I believe that healthcare is far too expensive. Unfortunately, the cost of healthcare moves in only one direction – up. The reason for this strange behavior is the complete absence of the usual market forces of competition and supply and demand in the health care market (source). It is not that health care is somehow uniquely exempt from the universal effects of supply and demand. Just look at those segments of the health care market that are subject to market forces, such as laser vision correction (also known as LASIK), and you see the steady decline in prices that one would expect from a maturing technology. The above cited research report on the high cost of American health care puts it this way: The overriding cause of high U.S. health care costs is the failure of the intermediation system — payors, employers, and government — to provide sufficient incentives to patients and consumers to be value–conscious in their demand decisions... Translation: If health care consumers were more price conscious, then prices would fall.

In the upside-down world of government run healthcare, too many hospitals is a bad thing, and hospitals need to be closed. Too many MRI machines within a community is a bad thing, and the extra machines must be removed. And too many doctors in a community is a bad thing, and the doctors must be relocated. In countries with national health insurance, all of the above are strictly controlled and the result is a form of rationing of healthcare. Long waiting lists and scarce supply of expensive technology is the norm. In America, 37 States already have government imposed restrictions in the acquisition and deployment of expensive technologies and building or expanding healthcare facilities in the form of “certificates of need” that are are used to limit the supply of health care in a given region. If market forces were allowed to operate, then an abundance of supply would lead naturally to a decline in cost. Instead, governments fear increased supply will lead to “over-utilization”. In short, the problems that exist within the US healthcare system are a consequence of too much government, and cannot be solved by even more government.

Surprisingly, “Sicko” traces the origins of the current healthcare dilemma to Richard Nixon (a Republican). He, in 1973, signed legislation creating Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs). But rising healthcare costs were already a problem in the 1970s, and that is the reason why HMOs were created. In actuality, out-of-control healthcare costs traces its roots back to 1942, when Roosevelt (a Democrat) pushed through legislation that imposed high taxes on corporate earnings but allowed health benefits to be written off as a tax-deductible business expense. This is why we now have the bizarre situation of health insurance being tied to employment, and the unfortunate situation dramatized in “Sicko” of many people feeling trapped in unrewarding jobs for fear of losing their health benefits. "Imagine if auto insurance worked the same way," says Bob Moffit of the Heritage Foundation. "So, if you lost your job, you could no longer drive. That would be profoundly absurd." Because the employer was now paying for health insurance, not the employee, a critical disconnect was made between care and cost. It encourages people to engage in behaviors detrimental to their health because they have no real appreciation for the costs of those behaviors, and the overutilization of care by individuals who believe someone else is footing the bill. In short, it planted the seed for the runaway healthcare costs that we are experiencing today.

Market-based reforms have been slow in coming, but we are starting to see some initiatives that look promising. Among the most promising new offerings are Health Savings Accounts (HSAs). With an HSA the employer deposits funds into a savings account that the employee controls. The employee can spend these funds on any healthcare-related expense, or he can allow the funds to accumulate. If the employee’s expenditures exceed a certain amount with a given timeframe, then a high-deductible insurance plan kicks in to cover them. The key to this plan is turning control over to the consumer. He now becomes aware of costs, because he is paying for them out of his savings account. He is thereby incentivized to get the maximum value for his healthcare dollar. If individuals are responsible for the consequences of unhealthy behaviors, then they will be more likely to adopt healthier lifestyles. In his book "Call to Action" Hank McKinnell writes "[T]he cornerstone of healthcare reform is to empower consumers of health services with as much information and market power as possible. The best way I know to create empowered patients is though the creation of incentivized personal health accounts that unleash the benefits of an ownership society."

In the movie “Sicko” the prime advantage of national health insurance is the ability to get the care you need without having to worry about the cost. But this is an illusion. In the real world somebody always has to worry about cost. In the case of national health insurance, it is the State. They deal with costs the only way governments can, by targeting the quantity of care (ie certificates of need). Fewer doctors, fewer hospitals, and fewer MRI machines. In short, by rationing care. In a market-based system, there are other ways of dealing with cost. Henry Ford realized that there was little point in building an automobile that the average man could not afford. By the same token, what’s the point of an MRI (or drug, or operation) that the average man cannot afford? Costs have soared because they could. Traditional health insurance would continue to pay for care no matter how high costs climbed. But if you empower consumers to shop for medical care the same way they shop for automobiles, that would introduce competition into the market, and drive down costs.

No comments:

Post a Comment